It’s always a strange thing when someone so significant within an industry passes away. The industry discussion is huge, yet outside it, it may not even create a whisper.

You may not even know who Zaha Hadid is. Or was.

She died unexpectedly this past week, age 65. Whilst many professionals aim for retirement around this age, her work (already at a high volume) was actually becoming more prolific.

So who was Zaha?

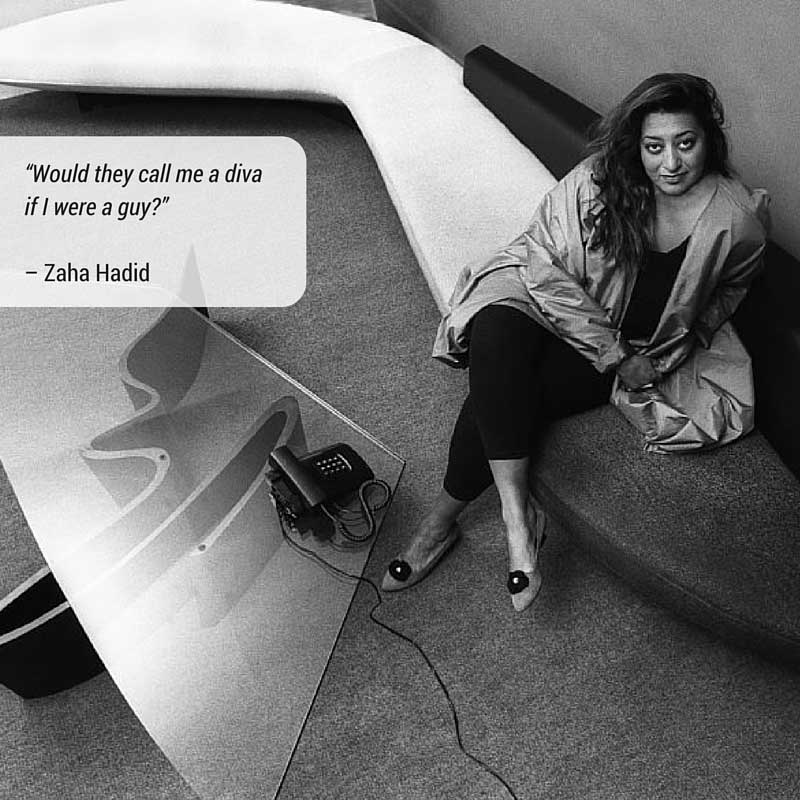

The diva

She’s been accused of being more sculptor than architect. Of having no concern for the actual experience or functionality of her buildings. Of ignoring the end user, the occupant, the client, the budget, all in pursuit of creating iconic works.

Her work has been called wasteful and monstrous. Lacking a relationship with its context. Ignoring its location altogether.

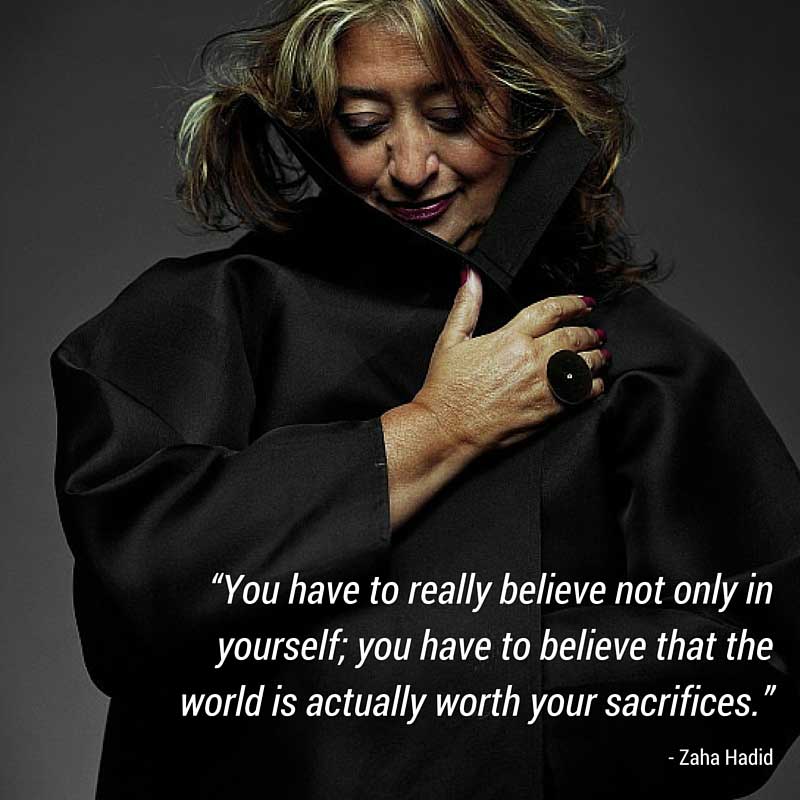

She has been called difficult, arrogant, pushy, loud, opinionated … a diva.

[Zaha Hadid in her office circa 1985 – Image Source: Dezeen]

The theorist

Zaha was born in Baghdad in 1950. Commencing architectural studies in Baghdad, she completed her studies in architecture in London. She began her own London-based architectural practice in 1980, age 30.

For the next 13 years, she became world-renown as the architect who never got anything built. Her projects were incredible – but they were all trapped on paper, in the computer. They were trailblazing, but they were all theoretical. The industry said “Yes, well the ideas are great … but they’re not buildable … [ie they don’t really count]”

And then, in 1993, the Vitra Fire Station at Weil am Rhein, Germany, was completed. It received high critical acclaim. Zaha Hadid had ‘arrived’.

[Photography by Hufton + Crow – Image source: Dezeen]

The architect

Zaha was a maverick, a visionary, a pioneer and a formidable, flamboyant, force. Her work was not only limited to buildings – she designed and created furniture, jewellery, and many other works. She was definitely outspoken – about architecture in general, and its role in our lives and societies, as well as being a female architect in an industry that pointed this out all the time.

She was the first woman and Muslim to be awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize (Architecture’s “Nobel” Prize) in 2004. She won many notable and highly coveted awards for her buildings. And in 2015, she received the RIBA Gold Medal – England’s highest architectural honour recognising a lifetime contribution to the industry. She was the first woman to be awarded in her own right since the award commenced in 1848 (and whilst well deserved, it says volumes more that industry took this long to award a female architect).

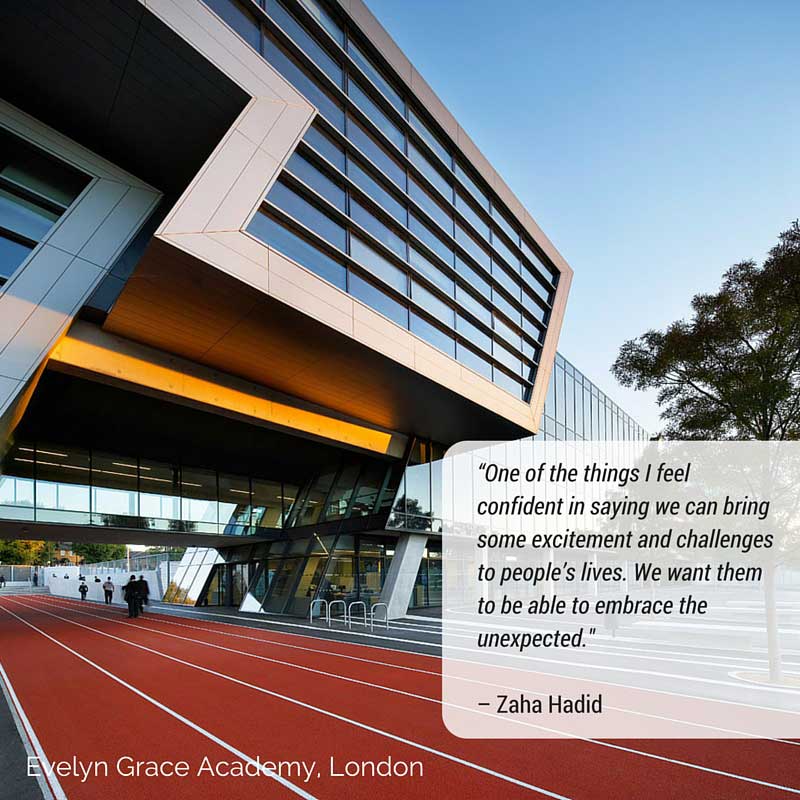

[Photography by Hufton + Crow – Image source: Dezeen]

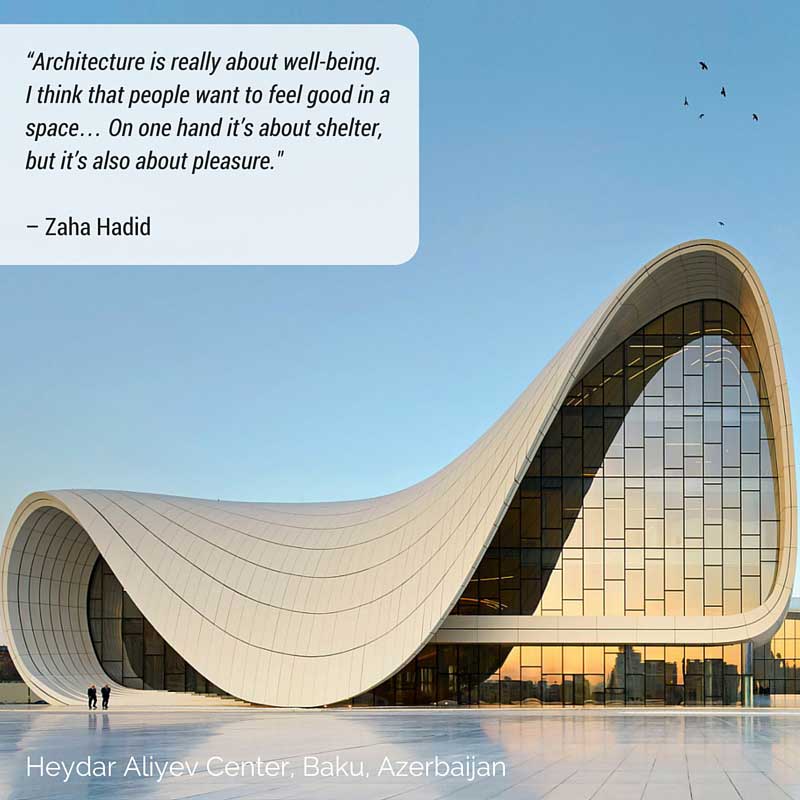

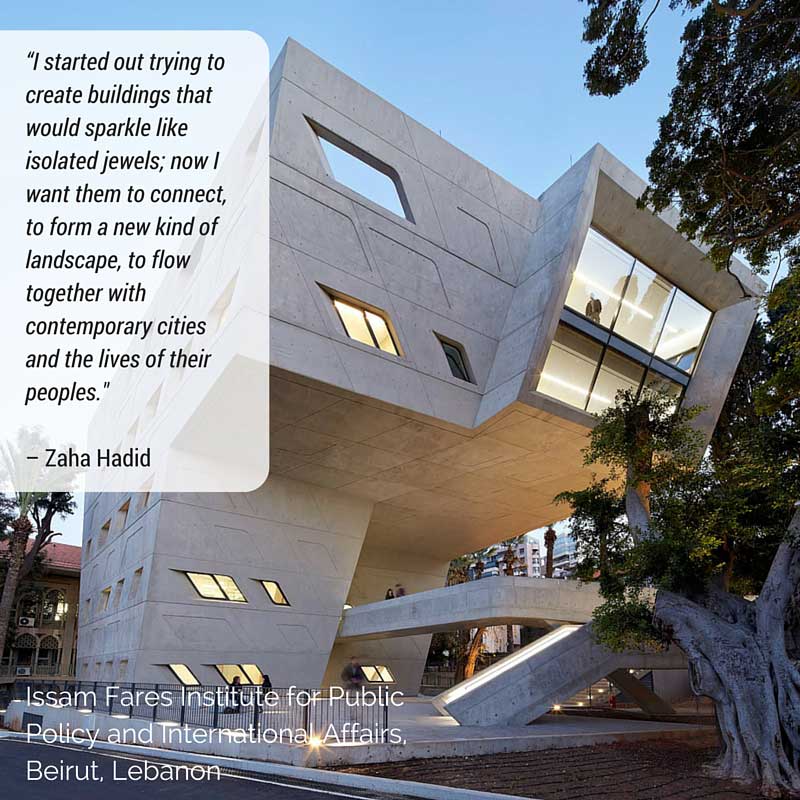

The buildings

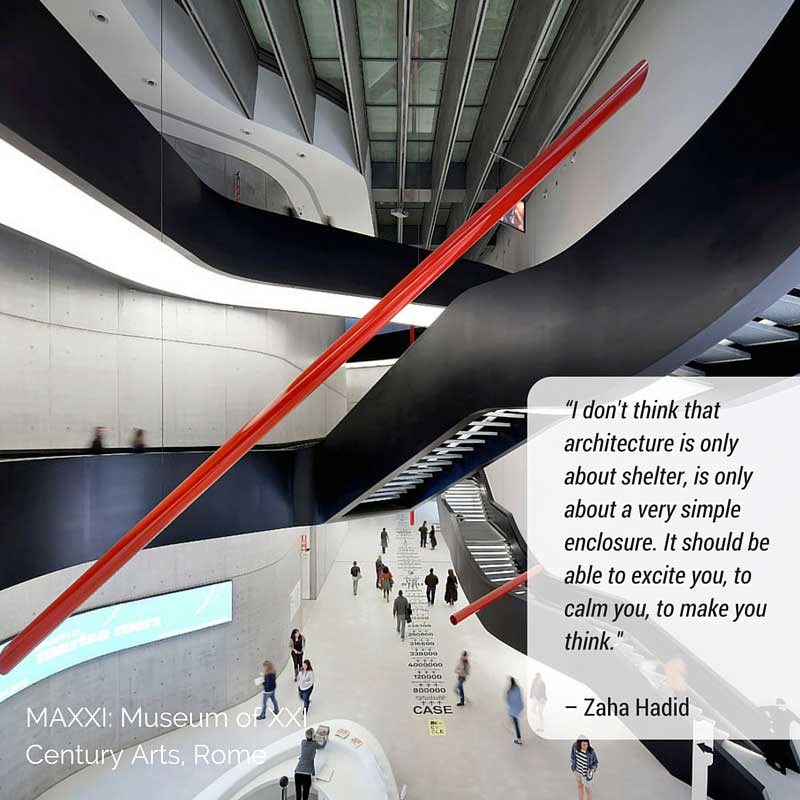

The consistent theme that exists in Zaha’s work is one of fluidity. Her buildings appear like frozen motion. Be it deconstructing, sharp and planar as in the Vitra Fire Station, or sensuous, flowing and voluptuous as with Azerbaijan’s Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku.

She seriously pushed boundaries. Her research was endless, with multiple solutions to any one problem. Each individual building appears as a snapshot in a much bigger process of her exploration, study, and uncovering of ideas about space, volume, light and our interaction with each.

In this frozen motion, her buildings seem to defy gravity. They are likened to non-building things like Marilyn Munroe’s wind-blown skirt over the subway grate, or shards of ice.

[Photography by Hufton + Crow – Image source: Dezeen]

If you think about what it takes to conceive these designs … that’s one hurdle. To think them out in three-dimensions, and visualise the spaces and shapes they’ll create, and how they’ll house the functions they need to.

But then think about how you get them drawn? To resolve the details. Design the structure. Sort out how the services will run, and how you’ll satisfy various building laws and codes.

And then you need to document them sufficiently to explain and convey that vision at a detail level so they can be costed, and planned.

And to get them built? The structure, the materials, how they all get put together, and physically held up. The plumbing, the electrical, making them waterproof.

If it’s not coming across, that’s where my mind boggles. Between the dream and the reality is a mountain of personal agendas, physical obstacles, pragmatic resolutions and legislative boxes to tick. Work of this scale takes a passion, drive and vision that is incredible to sustain over such a huge volume of work.

Whether she was simply a Demanding Diva or Design Role Model is up to you to decide.

I have always found her work dramatic, dynamic and exciting both internally and externally – however, I haven’t visited any of her finished works in person (yet) to make my final judgement. (I totally disliked Frank Lloyd Wright’s work during my studies at uni, and then fell madly in love with it after visiting them personally).

You can’t dispute the sheer amount of energy, determination and conviction – as well as talent, skill and experience – required to execute projects as she did.

And I suspect that, as a man, the dialogue about her personal style in doing that, would have been significantly different.

[Photography by Hufton + Crow – Image source: Dezeen]

Whilst the first 13 years of her solo career saw no projects built, the last decade has seen a HUGE amount of projects built, with many (many, many) more in the works. It was like she was gaining momentum! Her first Australian project is actually navigating a contentious approval as we speak.

Zaha’s ‘starchitect’ status meant her name could add real estate value, and this was helping her work enter mainstream residential projects with developers leveraging her involvement for faster sales and an iconic development.

On a personal note

I remember seeing Zaha’s work published in architectural magazines I devoured during my years at uni. Her Vitra Fire Station wasn’t built until after I’d started university, and even during those years, she only had a couple of built projects published … and lots more unbuilt works.

So it all seemed very fantastical. Incredible, but it sat at total odds with the work that was being built everywhere else. She was a renegade, and physically she appeared as this flamboyant, beautifully dressed and strong looking woman, who was coming up with some AMAZING ideas – but no one was willing to build them.

Later, when I was living in London in 1999 and working in an architectural practice, I asked my fellow colleagues what was involved in getting a job at Zaha Hadid’s practice.

“Oh, you don’t want to do that, you’ll never see the light of day.” (Work of that scale and type takes BIG hours to deliver. That’s no surprise – I was pretty used to working massive hours, having come from a pre-Olympics Sydney and being a graduate working for Tonkin Zulaikha. I was at the office very long days, lots of nights and weekends – and LOVED it!)

“She only hires young boys – office is full of them.” (Her office is actually 40% female – with many women in senior positions – much more than the industry standard).

The thing is … work that is as avante garde as hers is … that pushes the frontiers of what is possible … and that is delivered with a brave, deliberate, almost forceful and uncompromising commitment to making them happen … is going to ruffle feathers. Generate rumours. Create urban myths and negative feedback.

All change does. In any industry.

My impression of Zaha was that she didn’t care much about this, about what the industry thought of her, or whether the work got built or not. And that her lack of worrying about what others thought was often what ruffled feathers the most.

What she seemed to care about most was the work … that it kept improving, kept testing, pushing and expanding. That she (and her team) were always giving their best in doing that. No mediocrity. And in that, she kept growing as an artist and as a creator. And that she challenged the way we thought about the spaces around us, and how we interact with them. That she kept the conversation going. To me, this was her real interest and passion.

Architecture treads a very fine line between art and function. There are always strong opinions about which side of that line it “should” really land. I love that she played with that line in her work, and always got everyone talking about the role of architecture in our lives.

The unfinished legacy

So what about all that work still underway? Well, with over 400 staff, Zaha had built up a very strong practice, with a big senior team of Directors, Associate Directors and Associates. Her partner, Patrik Shumacher, has worked by her side for the last 25 years, and his hand is in every one of her projects.

So her legacy remains strong – her way of working, her design theories, and her expectations – and I expect we will see her style stay equally strong.

Whilst researching for this blog post, I found this quote of hers:

“Of course I believe imaginative architecture can make a difference to people’s lives, but I wish it was possible to divert some of the effort we put into ambitious museums and galleries into the basic architectural building blocks of society.”

– Zaha Hadid

And that’s what I wish we’d had the chance to see.

Her extreme imagination and convention flipping, backed by her uncompromising determination to explore and push boundaries, could have made a big impact in less glamorous projects such as social housing and hospitals.

One of her unbuilt recent works included an apartment in a Ronald McDonald Charity House, Hamburg that used materials to explore texture and create space for play, as a way of creating room for families and siblings to communicate and be together (whilst supporting seriously sick children in a nearby hospital).

[Image source: Designboom]

She bucked the system – a very proper, established and formal English system – and explored what was considered impossible.

[Photo by Steve Double – Image source: Archdaily]

Whatever you thought of Zaha Hadid – if you even thought of her at all – she left her mark. An indelible, sexy and viviacious stroke of ink on the drawing board of architectural history.

She just kept on being true to what she wanted to do, not worrying about whether she was liked – just whether what she was doing was any good.

I think there’s a great lesson in that for all of us. Vale Zaha.

To listen to a great interview from the ABC’s Blueprint for Living program discussing Zaha’s work: CLICK HERE

With over 30 years industry experience, Amelia Lee founded Undercover Architect in 2014 as an award-winning online resource to help and teach you how to get it right when designing, building or renovating your home. You are the key to unlocking what’s possible for your home. Undercover Architect is your secret ally

With over 30 years industry experience, Amelia Lee founded Undercover Architect in 2014 as an award-winning online resource to help and teach you how to get it right when designing, building or renovating your home. You are the key to unlocking what’s possible for your home. Undercover Architect is your secret ally

Leave a Reply